natural disasters in NEOM

I was recently in Essen for the release of NEOM, which is what the game previously known as Draftopolis or City Draft (written about extensively here and mentioned briefly here) has become after being published by Lookout Games. And while overall I've been overjoyed with the response, I've seen a few comments from people who dislike the inclusion of the disaster tiles in the game, and I realized that I haven't ever sat down to write out my thoughts for why I included the mechanic despite knowing that those tiles would be controversial. Without further ado, here's what I was thinking:

I was recently in Essen for the release of NEOM, which is what the game previously known as Draftopolis or City Draft (written about extensively here and mentioned briefly here) has become after being published by Lookout Games. And while overall I've been overjoyed with the response, I've seen a few comments from people who dislike the inclusion of the disaster tiles in the game, and I realized that I haven't ever sat down to write out my thoughts for why I included the mechanic despite knowing that those tiles would be controversial. Without further ado, here's what I was thinking:

1. Theme

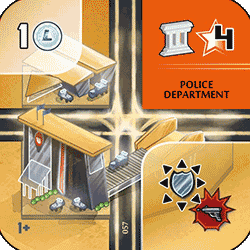

First off, they're a thematic home run for anyone who's played SimCity, and even for those who haven't they tend to be very relatable. Of course you would have to plan around natural disasters if building a city! The relationship with Fire and Police Departments is also apparent, and those are a natural way for adjacency (and therefore placement) to matter, which makes the city grid more interesting.

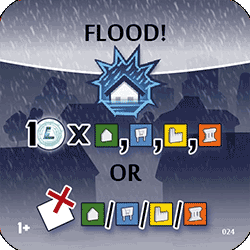

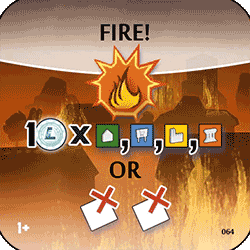

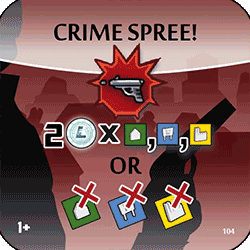

The different effects of the individual disaster tiles are also very thematic - when calculating penalties, all of them only count (i.e. cause damage to) building tiles, as that's what a city would largely be responsible for. In addition, Crime Spree doesn't count Public tiles, as who's going to rob a government building or a power plant? Fire is unique in that it allows Resource tiles to be sacrificed, given that it's easy to imagine the Raw Goods burning away (particularly in the case of Wood or Oil!). Each of these differences will come into play in how best to prepare and deal with the individual disasters, giving each Generation of the game a different flavor.

The different effects of the individual disaster tiles are also very thematic - when calculating penalties, all of them only count (i.e. cause damage to) building tiles, as that's what a city would largely be responsible for. In addition, Crime Spree doesn't count Public tiles, as who's going to rob a government building or a power plant? Fire is unique in that it allows Resource tiles to be sacrificed, given that it's easy to imagine the Raw Goods burning away (particularly in the case of Wood or Oil!). Each of these differences will come into play in how best to prepare and deal with the individual disasters, giving each Generation of the game a different flavor.

2. Risk/Reward

Without disasters in the game, there would be very little tension to how you build your city. Residential strategies, for example, would be about blindly taking every Residential tile you see and fitting them together in whatever configuration comes together. But with disasters in play, the greedier (i.e. heavy Residential or to some extent heavy Industrial) strategies become much more interesting - do you take that Residential tile knowing that you won't be able to afford the Fire if it happens this turn? Do you let your neighborhood grow as quickly as possible in all directions, knowing that will make it harder to protect with Fire and Police Departments, or do you try and keep it contained to one area of the city?

Without disasters in the game, there would be very little tension to how you build your city. Residential strategies, for example, would be about blindly taking every Residential tile you see and fitting them together in whatever configuration comes together. But with disasters in play, the greedier (i.e. heavy Residential or to some extent heavy Industrial) strategies become much more interesting - do you take that Residential tile knowing that you won't be able to afford the Fire if it happens this turn? Do you let your neighborhood grow as quickly as possible in all directions, knowing that will make it harder to protect with Fire and Police Departments, or do you try and keep it contained to one area of the city?

In addition, there are a variety of mitigation strategies available in the game that I'll discuss later - but discovering how to best execute these is a significant contributor to why the game has as much depth as it does, and why there are 13 people who have each completed over 100 games in the online prototype (not even counting solitaire or bot games!). Even once you've mastered these strategies you'll find that there are certain Cornerstone tiles that will tempt you into making risky plays once again, and sometimes you'll get away with them, and sometimes you won't.

3. Psychology

So why don't the disasters just happen automatically at the end of the generation or whatever? Well, if you play with the same group of players consistently, you can start to learn their tendencies as to how much they like playing disasters. Once you've seen the disaster tile for a given Generation, you can track it as it moves around the table, and weigh whether each person might want to take it (based on a combination of their proclivities and their own vulnerability to that disaster - with higher vulnerability making them more likely to pull the trigger).

Relatedly, there are two ways in which disasters directly provide psychological tension for players who understand when they're currently vulnerable: 1. when a new Generation is starting and the packs are being dealt out (as you hope to open the disaster so that you can play it before anyone else) and 2. when you're knowingly leaving yourself vulnerable and hoping no one punishes you for it as the packs move around the table. Granted, this requires knowing what the disaster for the current era will do without having it in front of you, so I do wish that the game had included some reference cards with that information - but in the meantime you can download a Disasters + Cornerstone Icons reference card that I've uploaded to BoardGameGeek.

Relatedly, there are two ways in which disasters directly provide psychological tension for players who understand when they're currently vulnerable: 1. when a new Generation is starting and the packs are being dealt out (as you hope to open the disaster so that you can play it before anyone else) and 2. when you're knowingly leaving yourself vulnerable and hoping no one punishes you for it as the packs move around the table. Granted, this requires knowing what the disaster for the current era will do without having it in front of you, so I do wish that the game had included some reference cards with that information - but in the meantime you can download a Disasters + Cornerstone Icons reference card that I've uploaded to BoardGameGeek.

4. Interaction

In 7 Wonders, when you can see that someone across the table is doing incredibly well, there's nothing you can do about it other than plead with the people next to them to take the tiles that their strategy desires (usually science). In NEOM, when someone is doing particularly well (usually as a result of a greedy strategy like heavy Residential), you can always hope to pick a disaster tile that takes them down a notch.

That said, it was very important to me that the disasters in NEOM are non-targeted (similar to Attack cards in Dominion). When games have targeted attacks, discussions often devolve into multiple players trying to convince the table that they're not doing well, which I find tedious at best and downright annoying at worst (it especially bothers me that I can't help but engage in this as well, as it's the right play if you're trying to win - a particular game of Small World with my brother comes to mind!).

So as I mentioned earlier, there are actually a variety of ways to handle disasters in NEOM, and learning them is a big part of improving as a player. Here are the major categories, from the most self-evident to the least:

1. Organize around Fire and Police Departments

Unsurprisingly, building around the tiles that specifically protect against disasters will greatly reduce your vulnerability. The trick here is that you'll have to arrange the rest of your city to maximize how many relevant tiles each Department can hit. This means surrounding your Fire Departments with buildings of any type and, more importantly, your Police Departments with just Residential, Commercial, and Industrial tiles. That's sometimes easier said than done, however, so one effective technique can be to just focus your tiles of those types around your City Center, and then take advantage of the covering rules to place a Police Department on top of the City Center either late in the 2nd Generation or early in the 3rd.

Unsurprisingly, building around the tiles that specifically protect against disasters will greatly reduce your vulnerability. The trick here is that you'll have to arrange the rest of your city to maximize how many relevant tiles each Department can hit. This means surrounding your Fire Departments with buildings of any type and, more importantly, your Police Departments with just Residential, Commercial, and Industrial tiles. That's sometimes easier said than done, however, so one effective technique can be to just focus your tiles of those types around your City Center, and then take advantage of the covering rules to place a Police Department on top of the City Center either late in the 2nd Generation or early in the 3rd.

2. Invest heavily in Resources

One aspect that makes Resource tiles much better than they might originally seem is that they aren't vulnerable to any of the three disasters, meaning that someone who invests heavily in them will have much more manageable penalties than someone who doesn't. In addition, other players are liable to buy the Raw Goods from you, which can add up even if the individual trades are only worth an L-Coin or two (and players are much more likely to be willing to shell out for the cheaper Raw Goods than they are for Goods from the more expensive tiers!). Finally, Public tiles are also notable in that they dodge Crime Spree, so a city focused around those (perhaps with Civic Center) will have a much easier time overall, even without Fire or Police Departments.

One aspect that makes Resource tiles much better than they might originally seem is that they aren't vulnerable to any of the three disasters, meaning that someone who invests heavily in them will have much more manageable penalties than someone who doesn't. In addition, other players are liable to buy the Raw Goods from you, which can add up even if the individual trades are only worth an L-Coin or two (and players are much more likely to be willing to shell out for the cheaper Raw Goods than they are for Goods from the more expensive tiers!). Finally, Public tiles are also notable in that they dodge Crime Spree, so a city focused around those (perhaps with Civic Center) will have a much easier time overall, even without Fire or Police Departments.

3. Prioritize tiles with instant benefits

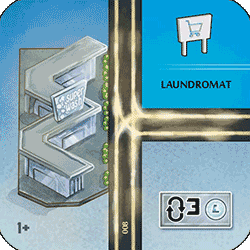

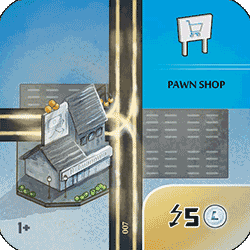

At first blush, a tile like Pawn Shop might seem significantly worse than other Commercial tiles like Laundromat - the former gives $5 immediately, but the latter will give $9 over the course of the game, equivalent to an extra 2 VPs. And without disasters, that would generally be true, but that's where the second option on each disaster tile comes in. Instead of paying money, you can always choose to sacrifice tiles, even if you have enough money on hand. And there's next to no drawback to sacrificing a tile like Pawn Shop that has already provided all of its value up front. So when you consider that a Flood might cost you $5 or $6, and you add those savings to Pawn Shop's immediate $5, it actually ends up providing more overall money than Laundromat in many situations.

At first blush, a tile like Pawn Shop might seem significantly worse than other Commercial tiles like Laundromat - the former gives $5 immediately, but the latter will give $9 over the course of the game, equivalent to an extra 2 VPs. And without disasters, that would generally be true, but that's where the second option on each disaster tile comes in. Instead of paying money, you can always choose to sacrifice tiles, even if you have enough money on hand. And there's next to no drawback to sacrificing a tile like Pawn Shop that has already provided all of its value up front. So when you consider that a Flood might cost you $5 or $6, and you add those savings to Pawn Shop's immediate $5, it actually ends up providing more overall money than Laundromat in many situations.

This can occasionally backfire, though, if no one plays the Flood in the first Generation and then you end up having to pay for your Pawn Shop when Fire and/or Crime Spree ends up happening. Your best option in that case is probably to sacrifice it to the Fire along with one of your Resource tiles (as unlike Flood or Crime Spree, Fire allows the sacrificing of any tile). Another interesting option, if it becomes clear that it's about to cost you additional money in a Crime Spree, is that you can always play another Commercial tile on top of it, thereby reducing your overall vulnerability.

This can occasionally backfire, though, if no one plays the Flood in the first Generation and then you end up having to pay for your Pawn Shop when Fire and/or Crime Spree ends up happening. Your best option in that case is probably to sacrifice it to the Fire along with one of your Resource tiles (as unlike Flood or Crime Spree, Fire allows the sacrificing of any tile). Another interesting option, if it becomes clear that it's about to cost you additional money in a Crime Spree, is that you can always play another Commercial tile on top of it, thereby reducing your overall vulnerability.

4. Skip a tile type entirely until after Crime Spree

Crime Spree's alternative penalty is to sacrifice a Residential tile, a Commercial tile, and an Industrial tile. However, if you don't have one or more those tile types, you can ignore that portion of the penalty, making it a valid strategy to say, forego building any Residential tiles until after the Crime Spree occurs (which tends to be early in the Generation). If the Commercial tile that you sacrifice is a Pawn Shop or a Collection Agency, or if the Industrial tile that you sacrifice is one that's obsolete because you already produce that Good in another way (most commonly because you've built a Modern Factory or Modern Foundry), so much the better. In fact, with proper preparation it's very possible to only lose 1 or 2 VPs from your eventual score when sacrificing tiles to Crime Spree.

Crime Spree's alternative penalty is to sacrifice a Residential tile, a Commercial tile, and an Industrial tile. However, if you don't have one or more those tile types, you can ignore that portion of the penalty, making it a valid strategy to say, forego building any Residential tiles until after the Crime Spree occurs (which tends to be early in the Generation). If the Commercial tile that you sacrifice is a Pawn Shop or a Collection Agency, or if the Industrial tile that you sacrifice is one that's obsolete because you already produce that Good in another way (most commonly because you've built a Modern Factory or Modern Foundry), so much the better. In fact, with proper preparation it's very possible to only lose 1 or 2 VPs from your eventual score when sacrificing tiles to Crime Spree.

Lastly, if you're pursuing a Treasury strategy you may want to sacrifice tiles even if you'll have to lose a tile of all three types, because the most important thing for your city at that point is just your current money total, and if you can keep that high enough you can win despite losing a Residential, some income, and a Processed Good.

Despite all this, if you know that drafting disasters won't be a hit with your group, you could try either allowing them to be sold and discarded or just try replacing them with other tiles from a higher player count, and then and either have them always happen at the end of their respective Generation or just not happen at all. I actually haven't tested those variants, so if you do end up preferring them, or if you come up with another idea, please let me know in the comments!

P.S. If you're curious to try NEOM, feel free to check out the online prototype, or if you'd just like to read more about it, you can visit the BGG Page.

building a better drafting game

I've been fascinated by board games that revolve around drafting for years now, and in early 2011 I wrote a post on the pillars that make these games click. Not long after that I started working on a game (then called City Draft) that would be strongly inspired by a few key influences: 7 Wonders for the mechanics and structure, Carcassonne for the idea of placing tiles in a grid, and SimCity for the theme. I touched upon it briefly in an October 2011 post that said it was improving steadily, and I've been working on it off and on (under the name Draftopolis) ever since. I've created an online prototype for playtesting that has seen almost 2000 games completed with at least a dozen players clocking in at over 100 games apiece. The rapid feedback and iteration cycles enabled by this level of playtesting mean that the game is currently in fantastic shape.

I've also had years to mull over the design of Draftopolis, and I wanted to take some time to list out the improvements that I feel it makes over the game that first brought this genre to the forefront: 7 Wonders. Note that 7 Wonders is considered the 17th best board game of all time in the widely respected BoardGameGeek rankings, and I completely agree with that rating. I'm also a huge fan of the designer, Antoine Bauza, who has released several masterpieces of elegant design in the past few years. That said, no game is perfect, and here's a list of some issues I have with the game that I've tried to address:

1. Guilds are based largely on factors outside of your control.

For a variety of reasons, the decks for each age in 7 Wonders are fixed from game to game. The one exception is that each time you play, you randomly select some guilds to shuffle into the Age 3 deck. These guilds mostly provide variable point bonuses based on the types of buildings the players to your left and right have built. This means that finding effective guilds feels largely random since you can't plan your strategy around them and each individual guild is only good if your neighbors happen to be pursuing certain strategies. The best you can do to influence this is to ensure that you have the appropriate resources to play guilds that would be good for you, but even then there's a good chance that a given guild isn't in the deck at all.

There's a large setup cost to having a selection of cards that are separately randomized at the start of each game, but with a few tweaks I felt that the potential payoff was more than worth it. The simple solution was to move the guilds to the first era (calling them "cornerstone" tiles instead) and to make them dependent on your own strategy rather than those of your neighbors. One example would be the Environmental Agency, which is a Civic building that grants victory points for spaces in your grid that 1) don't have a building and 2) have no nearby pollution. This leads to cities with wide open areas of undeveloped nature that either purchase all of their goods from other players or carefully position their industry in a corner surrounded by their other buildings. With 30 different cornerstone tiles that could show up, successive games of Draftopolis feel very different from start to finish.

There's a large setup cost to having a selection of cards that are separately randomized at the start of each game, but with a few tweaks I felt that the potential payoff was more than worth it. The simple solution was to move the guilds to the first era (calling them "cornerstone" tiles instead) and to make them dependent on your own strategy rather than those of your neighbors. One example would be the Environmental Agency, which is a Civic building that grants victory points for spaces in your grid that 1) don't have a building and 2) have no nearby pollution. This leads to cities with wide open areas of undeveloped nature that either purchase all of their goods from other players or carefully position their industry in a corner surrounded by their other buildings. With 30 different cornerstone tiles that could show up, successive games of Draftopolis feel very different from start to finish.

2. Science is purely all or nothing.

One of the core qualities of a solid drafting game is that players value the same cards significantly differently based on their position. In 7 Wonders, this manifests to an extreme with Science, which is nearly useless unless you commit heavily to it. Often you find yourself in a position where the player behind you is picking up Science cards and the game comes down to whether you're willing to spend early picks hate drafting them (torpedoing both your chances) or whether you let them through, nearly guaranteeing their victory. And if you choose the latter option, everyone at the table blames you for letting them win.

In Draftopolis the role of Science is filled by Residential tiles, which are worth increasing numbers of bonus points when they're placed contiguously into neighborhoods. The key difference is that I later stumbled onto the idea of including a thematically appropriate rule (called the "Ghost Town" penalty) that states that cities without any Residential tiles lose 10 points, and cities with only one lose 4 points. With this, all players have a large incentive to at least dabble in Residential and competition is ensured for the high value tiles within that category. In addition, the bonus flattens out after the eighth Residential in a neighborhood (rather than continuing to grow exponentially) so that even a player who gets all of the Residential tiles still needs to earn points in other categories to win the game.

In Draftopolis the role of Science is filled by Residential tiles, which are worth increasing numbers of bonus points when they're placed contiguously into neighborhoods. The key difference is that I later stumbled onto the idea of including a thematically appropriate rule (called the "Ghost Town" penalty) that states that cities without any Residential tiles lose 10 points, and cities with only one lose 4 points. With this, all players have a large incentive to at least dabble in Residential and competition is ensured for the high value tiles within that category. In addition, the bonus flattens out after the eighth Residential in a neighborhood (rather than continuing to grow exponentially) so that even a player who gets all of the Residential tiles still needs to earn points in other categories to win the game.

3. Few viable paths to victory.

In the base set of 7 Wonders, there are only a few strategies that can consistently win games: mainly heavy Science (when it's underdrafted), Military (with pacifist neighbors), or resource heavy (leading into some high value Civic buildings). The Commercial (yellow) strategy has a tough time winning due to the poor exchange rate of money to victory points (3 to 1) and heavy Civic (blue) strategies simply can't compete with other plans that end up earning points more efficiently. That said, the Leaders expansion does a wonderful job of fixing this problem without adding significant amounts of complexity.

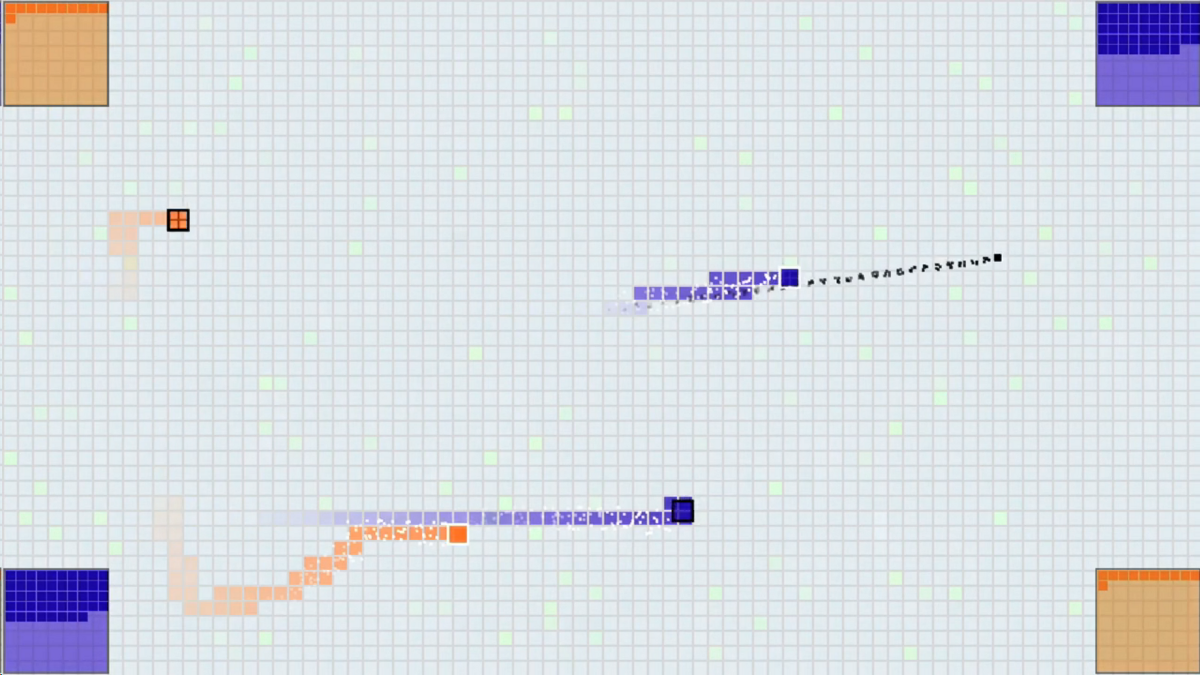

Draftopolis utilizes the cornerstone tiles and more favorable point conversions for money strategies (1 VP for each $2, with players capable of ending games well over $100) to open up the playing field. Residential-focused, Commercial-focused, and Industrial-focused strategies are all viable, as well as hybrid builds revolving around efficient tiles and/or one or more cornerstones. This display of the recent winning cities shows off the relative diversity of strategies that can do well.

Draftopolis utilizes the cornerstone tiles and more favorable point conversions for money strategies (1 VP for each $2, with players capable of ending games well over $100) to open up the playing field. Residential-focused, Commercial-focused, and Industrial-focused strategies are all viable, as well as hybrid builds revolving around efficient tiles and/or one or more cornerstones. This display of the recent winning cities shows off the relative diversity of strategies that can do well.

4. Limited play decisions.

After a card is picked in 7 Wonders, there are only three choices of what to do with it: play it, build a stage of your wonder, or sell it. As the wonder option is often unavailable due to resource constraints, and selling is rarely worthwhile, this leaves only one real choice most of the time.

By contrast, Draftopolis features a 5x5 city grid that each player is independently filling with their tiles, with available trade routes on either side that provide benefits when a road is connected to them. The choice of where to play early tiles can play a crucial role in how a city develops into the mid and late game. A key decision that I settled on early in the process was that tiles can't be rotated, as the combinatorial possibilities of tiles, placements, and orientations would result in analysis paralysis for a lot of players. I do feel that the placement decision layer adds significant skill to the game, and it does so without adding too much time since everyone decides where to put their tiles simultaneously.

By contrast, Draftopolis features a 5x5 city grid that each player is independently filling with their tiles, with available trade routes on either side that provide benefits when a road is connected to them. The choice of where to play early tiles can play a crucial role in how a city develops into the mid and late game. A key decision that I settled on early in the process was that tiles can't be rotated, as the combinatorial possibilities of tiles, placements, and orientations would result in analysis paralysis for a lot of players. I do feel that the placement decision layer adds significant skill to the game, and it does so without adding too much time since everyone decides where to put their tiles simultaneously.

5. Static sell values and trade costs.

In 7 Wonders, cards in later ages are significantly more powerful and valuable than early age cards. Yet the return for selling a card remains $3 throughout, and selling a card in the third era (for the equivalent of 1 VP) is an almost surefire way to lose the game. Similarly, the cost for purchasing a resource is always $3, which is a massive commitment early game and a relatively small pittance late.

Draftopolis scales both the trade cost and the sell price throughout the game, increasing by $1 per era. This softens the "noob trap" elements of the sell option, and commodity-focused strategies are more rewarding since each sale will bring in the equivalent of 2.5 victory points in the final era.

EDIT: After playtesting this rule some more, I've changed the design to use a $5 static sell value and trade costs that only depend on the tier of the commodity being sold. Both of these values can be listed directly on the playmat and players don't have to go through an additional step to calculate the cost or benefit of a potential trade or sale.

6. Players can only interact with their direct neighbors.

Being sandwiched between two resource light players in 7 Wonders can be devastating, as many buildings and wonders require multiples of a single resource in their cost. Situations where you know that someone across the table is running away with the game without any way to affect them can also be frustrating.

For Draftopolis, I originally allowed players to purchase resources directly from the bank at a steeper cost, but this added complexity and created awkward decision points where you had to decide whether it was worth it to pay extra to avoid helping out your neighbor. I eventually settled on a replacement solution of allowing resources to be purchased from anyone at the table with a $1 transport fee for each player between the seller and buyer. If a commodity such as Steel isn't being produced yet, then everyone is in the same boat of being unable to play tiles that require it. In addition, disaster tiles give players a way to affect players across the table, without introducing direct attacks or other mechanics that would call for political posturing.

For Draftopolis, I originally allowed players to purchase resources directly from the bank at a steeper cost, but this added complexity and created awkward decision points where you had to decide whether it was worth it to pay extra to avoid helping out your neighbor. I eventually settled on a replacement solution of allowing resources to be purchased from anyone at the table with a $1 transport fee for each player between the seller and buyer. If a commodity such as Steel isn't being produced yet, then everyone is in the same boat of being unable to play tiles that require it. In addition, disaster tiles give players a way to affect players across the table, without introducing direct attacks or other mechanics that would call for political posturing.

7. Militaristic neighbors can further invalidate strategies.

When a player wins with the military strategy in 7 Wonders, it's often because one or both of their neighbors chose to eschew building red cards at all, letting them get maximum military points with a very small investment. On the other hand, neighbors who are willing to fight for military superiority put a player into a decidedly worse position pretty much from the get-go.

Draftopolis allows full control over trade routes (by making it a permanent feature of the game board rather than a card that must be drafted) as well as the cross-table resource purchasing, so players have the tools to react to any situation that their neighbors might create for them. Sometimes trade routes will be hugely valuable, and sometimes it's better to cluster one's buildings to make them easier to protect with Fire or Police Departments. Complaints about table position have been few and far between in my experience.

8. The pass direction is inconsistent.

When I watch new players try out 7 Wonders, the number one rule I see them mess up is the swapping of the pass order in the second era. Even experienced players often forget which way the cards are being passed, which can slow down the game or cause issues with the packs as they travel around the table.

I originally had cards being passed the opposite way in the second era in Draftopolis, but eventually came to the conclusion that always passing left is simply better for the game. It's easy to remember and makes it clear which neighbor you should be paying attention to when settling on a plan. In games where you play your drafted cards immediately, you have perfect information about what strategies your neighbors are pursuing, and therefore you can always make an informed decision.

9. More players mostly just means more copies of the same cards.

This does ensure that you're playing the "same game" when there are more or fewer people, but it's also boring, and it relates directly to the next most common rules mistake that I've seen: people playing second copies of the same card. Double checking that each card you want to play doesn't have the same name as a card you already have is both time consuming and not particularly fun.

In Draftopolis, every tile is unique, and each additional player results in new possibilities and potential city configurations. There also aren't any rules that prevent the selection of a tile because of tiles already present in a city. Games with different numbers of players each have their own unique flavor, and certain strategies are slightly stronger or weaker depending on the number, further increasing the replayability of the game. For example, the Treasury is only available with five or more players, and it enables a strategy focusing on Commercial buildings that produce lots of upfront cash as opposed to a more traditional build favoring high income tiles.

In Draftopolis, every tile is unique, and each additional player results in new possibilities and potential city configurations. There also aren't any rules that prevent the selection of a tile because of tiles already present in a city. Games with different numbers of players each have their own unique flavor, and certain strategies are slightly stronger or weaker depending on the number, further increasing the replayability of the game. For example, the Treasury is only available with five or more players, and it enables a strategy focusing on Commercial buildings that produce lots of upfront cash as opposed to a more traditional build favoring high income tiles.

10. With 6+ players, you never see the same pack twice.

Last but not least, with six or more players in 7 Wonders, you'll never see the packs that you open ever again. And with seven players, there will be packs opened next to you that never make it to you even once. This cuts out a significant aspect of drafting strategy ("tabling" cards) and contributes strongly to the perception that there's nothing you can do about someone across the table who's doing well.

Of course, this problem is easy to "solve" by just adding tons of cards (or tiles) to each pack, but that comes with its own set of problems: choices being overwhelming, the play space getting too crowded, etc. For these reasons I started testing Draftopolis also with seven tiles per pack, but I soon settled on the sweet spot being eight. Any more and it starts getting difficult to fan them out in your hand, any fewer and you start losing the "tabling" aspect as mentioned above. With the maximum number of players (six) you still get a second tile out of each of your opening packs, and with three players you even get a third.

In conclusion...

Draftopolis is a game that borrows heavily from 7 Wonders in many respects while simultaneously attempting to strike out in a bold new direction. It plays quickly but has far reaching depth, and after hundreds of games I still find myself agonizing over turns with regularity. I'm also starting to think seriously about looking for a publisher, so hopefully you'll be able to play a tabletop version of the game sometime within a year or two. Thanks for reading and I'd love to hear other takes on both 7 Wonders and my proposed solutions in the comments!

indie interviews: ramiro corbetta on hokra

To my knowledge, it isn't yet common for games to be commissioned in the way that works of art were commissioned by patrons throughout history. Yet that's exactly how Hokra, by Ramiro Corbetta (with audio by Nathan Tompkins), came to be. Hokra is a 2v2 sports game where the teams are fighting over control of a single ball. When a player doesn't have the ball, she can sprint, and when she does, she can pass in any direction. Sprinting increases speed but removes the ability to change directions for a short while. Sprinting through an enemy player stuns him briefly and causes him to drop the ball. Scoring is achieved by maneuvering the ball into one of the team's colored zones in the corners, and counts whether or not the ball is currently in a player's possession. The first team to fill up the counter in their scoring zones wins.

I first played the game at IndieCade and instantly fell in love. A few simple mechanics (passing, zone control, sprinting, tackling) come together to make a deep and compelling multiplayer experience. The refined aesthetic calls to mind a top down view of a hockey rink and provides a simple backdrop for the competitive gameplay. If commissions to a single designer are going to result in games like this, I hope the practice continues to flourish.

Ramiro was gracious enough to take the time to answer some questions about the game below:

What inspired you to make Hokra?

When I began working on Hokra, I was just trying to program a simple passing mechanic. I had been playing lots of FIFA10 at the time (well, I still play it a lot), and to me passing is by far the most interesting mechanic in soccer games. So I put a square player on screen, then a smaller square ball. I was interested in getting the concept of passing in the direction you were pointing with an analog stick to feel just right, so I created simple 2D ball physics and a system where the longer you hold A, the stronger your pass will be. It was very straightforward, but that was the point. I wanted that feeling that when you made a good pass, you did it because you were very accurate. A friend of mine who is also into soccer was coming over one day, so I added a second square player and we tried moving around the “field” and passing the ball back and forth. The game (or, really, the toy) was already surprisingly compelling.

How did you settle on the victory condition of having the ball in your team's corners for a set period of time?

At this point, I decided that I should turn what I had into a proper game. Making it a two-on-two game was a no-brainer since I wanted a game about humans playing against each other and a one-on-one game wouldn't involve much passing. My first instinct was to make a game about scoring goals, or at least getting the ball to go through a goal, giving your team a point each time you did it. Before I even implemented that, I realized that in such a small field it would probably be more fulfilling to try to hold the ball over a “touchdown” zone than to just get it into a goal. I put the zones in opposite corners for symmetry. I assumed I'd come back later and change it because it wouldn't just work out. I really thought there would be a lot of iteration with the scoring conditions and the placement of the goals, but it turned out much better than I expected, so I stuck with it.

Why did you decide to make it a one button plus analog stick game?

The next step was making it so that players would want to pass. As in real life sports, I wanted players to be slower when they had the ball. In order to do that, I allowed players who don't have the ball to sprint. At first, you'd press A to pass and X to sprint, but a friend asked me how come I was using two different buttons seeing as you can't pass when you don't have the ball and you can't sprint when you do have the ball. I told him I had thought about mapping both actions to the A button, but had never gotten around to it, which is a pretty bad excuse. I made the change on the spot (it was a one-character change in my code). Some friends still complain that sometimes you are sprinting toward the ball and you end up passing it by mistake (I've made tweaks to attempt to fix that problem). They ask me to go back to the two-button setup. I quite like the fact that you only press one button, though. The game was originally commissioned by the NYU Game Center for the 2011 No Quarter Exhibition, where lots of people would be playing the game for the first time, and they'd be doing it in a public space. Many of those people would not be gamers. I'm sure you've noticed that when people who don't play games that much are told to press the X button, they have to look down at the controller to figure out which one is the X button. I didn't want that problem to get in the way of people who were playing Hokra for the first time. Analog stick + A button makes the game more approachable. I'm always happy to make my games more approachable if I don't have to compromise on depth to do it.

The next step was making it so that players would want to pass. As in real life sports, I wanted players to be slower when they had the ball. In order to do that, I allowed players who don't have the ball to sprint. At first, you'd press A to pass and X to sprint, but a friend asked me how come I was using two different buttons seeing as you can't pass when you don't have the ball and you can't sprint when you do have the ball. I told him I had thought about mapping both actions to the A button, but had never gotten around to it, which is a pretty bad excuse. I made the change on the spot (it was a one-character change in my code). Some friends still complain that sometimes you are sprinting toward the ball and you end up passing it by mistake (I've made tweaks to attempt to fix that problem). They ask me to go back to the two-button setup. I quite like the fact that you only press one button, though. The game was originally commissioned by the NYU Game Center for the 2011 No Quarter Exhibition, where lots of people would be playing the game for the first time, and they'd be doing it in a public space. Many of those people would not be gamers. I'm sure you've noticed that when people who don't play games that much are told to press the X button, they have to look down at the controller to figure out which one is the X button. I didn't want that problem to get in the way of people who were playing Hokra for the first time. Analog stick + A button makes the game more approachable. I'm always happy to make my games more approachable if I don't have to compromise on depth to do it.

Where did the name come from?

When I was first working on the game, I was calling it “the sports game.” Obviously that wasn't going to stick. As the No Quarter Exhibition approached, Charles Pratt, who curates the event, told me that he needed a name from me. After going through a bunch of ideas, including SquareBall (which I liked, but was already taken), I started looking at names of Indigenous Brazilian sports. I'm originally from Brazil, and there are a few words in our Portuguese that come from Indigenous Brazilian languages. I ended up finding this sport from northern Brazil called rõkrã, which is similar to field hockey. This isn't a sport I knew about growing up, but it's similar to field hockey (a coconut is used as a ball and it's played barefoot, which sounds pretty scary) and I liked how the name sounded. I changed the R to and H because, with an American pronunciation, Hokra sounds more like the original name than Rokra.

What's your favorite memory of playing or watching others play Hokra?

I have two really good memories. Toward the end of the night at the No Quarter Exhibition, a game that was being watched by maybe 15 people got extremely exciting. There was a lot of back-and-forth and the crowd was really getting into it, making loud “uuuuuhhhh” noises whenever somebody did something special. The game was really close, and when it ended the crowd broke into applause. At that point I felt like I had gotten the spectator aspect of sports right.

I have two really good memories. Toward the end of the night at the No Quarter Exhibition, a game that was being watched by maybe 15 people got extremely exciting. There was a lot of back-and-forth and the crowd was really getting into it, making loud “uuuuuhhhh” noises whenever somebody did something special. The game was really close, and when it ended the crowd broke into applause. At that point I felt like I had gotten the spectator aspect of sports right.

The second memory happened when the Hand Eye Society guys invited me to show the game in Toronto. It was July 4th and I was in Canada with two other NYC game developers who were also showing their games. At one point we ran the Canadian Hokra Tournament, and once we had a winning team a couple of us stepped up to challenge them for the North American tournament. The whole bar was watching the game, and when the Canadian team beat us, the entire place broke into “O Canada.” Some of my Canadian friends said that Hokra sparked a rare moment of Canadian patriotism.

What game designers inspire you the most and why?

Fumito Ueda was a big influence when I was starting out as a game designer. Playing Ico made me realize that I definitely wanted to create games for a living. It's interesting that now I make games that are really different, thematically, from his. But I think that his minimalist design aesthetic is still a huge influence over how I make games. I think that it's hard to find a game designer who isn't influenced by Miyamoto's work, but I still need to mention him here because of how brilliant some of his games are. Finally, these days, I'm probably most influenced by a game designer who happens to be a friend, too – Doug Wilson. His games, such as B.U.T.T.O.N. and Johann Sebastian Joust, are some of the most interesting multiplayer games I've played in a long time. His work is not only absolutely amazing, but it's also really inspiring, affecting how I make my games more than anybody else's work does.

You have won a prize. The prize has two options: the first is a year in Europe with a monthly stipend of $2,000, and the second is ten minutes on the moon. Which option do you select?

When I first read this question I thought it was ten SECONDS on the moon, so going to Europe seemed like an easy decision. Now that I know it's ten minutes it's much harder, but I think I'd still take the European trip. As amazing as the ten minutes on the moon would be, I think my life would change more by spending a year traveling around Europe while creating games. That is if $2000 per month is even enough to travel around Europe these days.

sprite wars, gamers vs evil, and PAX

After three ink cartridges, twenty five sheets of perforated business card paper, and a whole lot of work in Illustrator, the business cards are finally done. There are currently 50 unique cards, and I'll be bringing five copies of each to PAX (with the exception of a group of ten that lost one each of their comrades in the process, so those will be a bit rarer than the rest). I'm calling the game Sprite Wars, and the rules set is a fairly simple modification of Tic-Tac-Toe.

You're probably raising one eyebrow and muttering something like, "Interesting..." right about now. Why Tic-Tac-Toe, a game that no adult in their right mind plays with each other, that is solved and always results in a draw? Well, I had a few goals in mind for the game:

- Players should be able to learn it very quickly, ideally from just watching someone play.

- It should be playable in only a couple of minutes.

- It should only require a few cards per player.

- It can't require any sort of additional materials and should be playable on pretty much any small flat surface.

These are wildly different goals from most TCGs that you would find in your local store. Whenever I'm trying to make something that people can pick up extremely quickly, I find it makes a lot of sense to start from a game that everyone is familiar with and innovate from there. In this case, the image of little pixel characters surrounded by arrows pretty much instantly popped into my mind, which took me in the direction of using the rules and victory condition of Tic-Tac-Toe.

Those who follow me on Twitter might have seen me agonizing over the design of the front of the cards. I wanted something to ensure that people looking at the front would notice the back, ideally in an organic manner so that I wouldn't have to keep repeating "and look at the back too!" to everyone. Originally I had small text at the bottom saying "flip me over!", but it made the card feel cramped and I had to squeeze multiple things on one line. After a bunch of advice I ended up just going with some simple arrows on the sides; they don't explicitly tell anyone to turn over the card, but they hint at it and they nicely reference the arrows on the back that drive the gameplay.

That said, I now regret adding them. What I didn't realize is that I was going to have some issues with getting the printing to line up, especially on the fronts (which I printed second, regrettably after waiting a few days, giving the ink-laden paper time to warp). Without the arrows, small differences in alignment wouldn't have been noticeable. With them, it's sadly obvious, and worse, it "marks" the cards for the game because savvy players will be able to remember the arrow placement on their different cards and know what they're about to draw. Then again, this is just a free game on the back of my business cards, so it's really not that big of a deal, but it's a good lesson for the future.

All told it probably cost around $60 or $70 in ink and paper for 240 cards, which seems like a lot, but for full color, double sided cards with 50 different unique designs, I'm pretty happy with how it turned out. I'll be giving them out at PAX this weekend, so if you're there, say hi! I'll be a part of two talks at PAX Dev: Practical Systems Design in the Context of Darkspore (scintillating title I know) and Design Doc Do's and Don'ts, where I'll be talking about everything but traditional design docs. At PAX itself I'll be spending a lot of time at the SpyParty booth, or perhaps at the Cryptozoic booth as well, where they'll have some early copies of The Penny Arcade Game: Gamers Vs Evil, a game that I designed along with some help from Mike Donais and Matt Place.

It's firmly in the deckbuilding genre, and takes inspiration from games like Dominion and Thunderstone, but also adds its own twist to things with mechanics like facedown unique boss loot and player avatars that grant a special ability and determine the composition of your starting deck. I've been a huge fan of Penny Arcade for as long as I can remember, so it was a huge honor to design this game for them. Can't wait for people to get a chance to try it out!

the curse of cooperation

Cooperative multiplayer is an oft-underused method of allowing people to play games together in a more accessible and casual manner. People are starting to warm up to it, though, and recent years have seen a surge of cooperative board games, as well as digital games like Starcraft 2 and League of Legends that are embracing co-op vs AI as a valid way to experience the game. There's something nice about winning or losing together with your friends, especially when one isn't in the mood for the intensity and cutthroat qualities of a typical competitive experience.

That said, there's a particular problem that's endemic to cooperative board games, which is that the game will present players with a puzzle, hoping that the group will work together to find a solution, and instead the single most skilled or most experienced player will end up playing for the entire group. It's just much simpler for a single person to execute a strategy than it is to get everyone on the same page and let them arrive at the best course of action themselves. Many games give each player a hand of cards, but in the absence of a rule that prevents discussing those cards, they often are just laid openly on the table to save everyone the trouble of having to continually ask what everyone else has. If I remember correctly, Pandemic actually recommends laying the cards down on the easy difficulty and then asks that players hold them in their hand on medium and above, but still doesn't restrict players from talking about them. That does help a little; players at least get to feel somewhat involved when they're asked how many red cards they have rather than simply told what to do.

Not to say that those games aren't well designed and enjoyable overall. The list of games suffering from this problem is quite long: Pandemic, Forbidden Island, Ghost Stories, Castle Panic, Castle Ravenloft, and so on. Both Pandemic and Ghost Stories are heralded as some of the best cooperative experiences out there, especially when playing with people of roughly equal experience and skill levels. Still, any designer thinking about the cooperative space should have this problem at the forefront of their mind.

Of course, many games have also managed to solve this problem, either intentionally or as a side effect of another mechanic. There are three methods of varying degrees of commonality:

The traitor - Betrayal at House on the Hill, Shadows Over Camelot, Battlestar Galactica, etc. Add in the fact that one or more players are secretly a traitor and suddenly players are no longer keen on playing the game for everyone else. Or rather, no one's willing to let their turn be taken for them. Then again, adding in a traitor does add a competitive element to the game, which you may or may not want.

Real-time aspects - Space Alert is the king of this category. Not only are there hidden cards, but there's also a strict time limit and an audio track constantly throwing new challenges in the team's direction. Knowing this, Space Alert actually has the players appoint a captain, and everyone still gets to contribute fully because there's simply no way the captain has time to order everyone around.

Hidden information plus restricted communication - For example, adding a rule that says that players can't talk about the cards in their hand. Games seem to be hesitant to pull the trigger here, and I can't think of an example at the moment, although I'm sure there must be one out there. My guess is that it stems from concern that players will have trouble interpreting a rule like this, or worse that they'll outright rebel against it. Richard Garfield talked about this in a podcast on cooperative games and also mentioned the idea of "communication as a resource", which I've been thinking about ever since.

With the cooperative prison break game that I'm currently working on, there are two phases: the planning and the escape. For the planning phase players are forbidden to discuss the game at all, and cards are played face down, but each player has two tokens that they can spend to show everyone else a card from their hand and describe where they're stashing it. The goal is for players to try to work together as best they can, planning what they'll need for the escape, with that limited channel of communication.

When the actual escape begins, all restrictions on communication are lifted, but there's now a real-time element, with new obstacles showing up every fifteen seconds. Players have their objects in their hand and have to discuss what object or objects the group wants to use to solve that obstacle. Thanks to the timer combined with the hidden hands, players stay involved during this phase despite the open communication channels.

Initial playtesting has been good, and I'm confident that all players will be able to contribute throughout the game. Now to fine tune the rest of the mechanics...

the pacifist and the pugilist

Last Thanksgiving, I was drafting with a guy named Zak Walter who had invented a deck of what he called "draft conditions". They had evocative names like The Astrologist or The Pacifist and each one had a limitation on your drafting or your deckbuilding. Now, I'll never get tired of just straight up drafting Magic cards, but it was an interesting twist to the process as battles become more about the archetypes (who wins: the Pacifist or the Pugilist?) rather than the players. It also gave people a reason to draft fun decks, gave them an easy excuse when they lost, and just made the whole night a lighthearted affair.

Not long after that I took the most memorable conditions from that night, brainstormed up a bunch of my own, added a few from Dan Kline, and made my first set of twenty conditions. These things really need a more evocative name: draft limitations? draft personalities? draft avatars? dravatars? I don't know. Anyway, Friday night I was drafting down at the San Carlos PopCap offices (where Plants vs Zombies was made by an extremely small team) and we tried them out for the first time. We had twenty conditions and twelve players so I gave everyone a random one and then put the remaining eight face down in the center of the table. If you didn't like your condition you were allowed to swap with one of the conditions in the middle, but you could only do this once.

Not long after that I took the most memorable conditions from that night, brainstormed up a bunch of my own, added a few from Dan Kline, and made my first set of twenty conditions. These things really need a more evocative name: draft limitations? draft personalities? draft avatars? dravatars? I don't know. Anyway, Friday night I was drafting down at the San Carlos PopCap offices (where Plants vs Zombies was made by an extremely small team) and we tried them out for the first time. We had twenty conditions and twelve players so I gave everyone a random one and then put the remaining eight face down in the center of the table. If you didn't like your condition you were allowed to swap with one of the conditions in the middle, but you could only do this once.

Here was my initial set along with comments on how they played:

The Arkmaster - Each creature in your deck must share a creature type with another creature in your deck.

I have high hopes for The Arkmaster although no one had it on Friday. It forces you to make some tough decisions if you open a powerful creature early with a rare creature type like "Sphinx" and should make you reevaluate your priorities even for more common creatures based on their types.

The Ascendant - Each card you draft must have a higher converted mana cost than the previous card drafted, if possible.

Brad Smith had the Ascendant, and it seemed to work out beautifully, providing lots of interesting choices. If you're not excited about a pack, you can take the most expensive card, hoping to reset your restriction as long as the next pack doesn't have anything even more expensive. There was also a natural reset built in at the end of each pack with the basic land that's often a fifteenth pick, but your neighbors can wreak havoc with that by selecting it and passing you a spell last, forcing your restriction to carry into the next pack. Brad opened a Flameblast Dragon and then was able to pick up a Volcanic Dragon in the very next pack since there wasn't anything costing seven or more. He was undefeated and seemed to have a great time.

The Astrologist - Secretly write down a number before the draft. The converted mana cost of the cards in your deck must add up to that number.

Stone Librande had this one, and chose to write down 70. Despite a couple bombs like Grave Titan and Serra Angel, it ended up being too high, and he was forced to play two Stonehorn Dignitaries in order to stay at 40 cards. Those kept coming up against me when he would've preferred drawing cards with more action, and I was able to take him down in three close games. Otherwise his deck performed admirably.

The Banker - You must always take the most rare card out of the pack. (Foils beat cards out of the same rarity, otherwise you choose.)

This was inspired by the infamous MTGO "bottom right" drafts where you always take the card in the bottom right of the pack. No one had this on Friday, but I have a feeling it's one of the most harsh conditions, because you'll often spend a lot of time taking the worst uncommon out of every pack before you can finally start drafting commons. Might need a benefit to balance it out.

The Builder - Your life total is 5 plus one for each card in your deck with a converted mana cost greater than three.

No one had this either. I'm a little wary of it giving the player too much freedom right now. You can draft pretty much normally and still end up with 16-18 life, which should be plenty against the gimped decks of your opponents. I think I might change it to two life per expensive card and also increase the threshold to five mana and above. This one is a little weird because it's not a restriction as much as a temptation, but for now I'm giving it the benefit of the doubt.

The Celestial - Cards other than basic lands in your deck must have the sky visible in the art.

I enjoy the art based ones greatly, but this one does suffer from a lot of ambiguity. I'd say whether or not you can get away with using this one depends greatly on the group you're playing with. If they're easy going and are willing to trust the judgement of the player who has it then it's worth having.

The Compulsive - You can't draft a card that's the same type as the last card you drafted, if possible.

Laura Shigihara, who did all the music for Plants vs Zombies, had this one. I didn't get a chance to play her but I think her deck turned out well and she had a good time. I also enjoy how you can select the basic land to reset your restriction and open up your options for the next pack.

The Elitist - Each creature in your deck must have a keyword or ability word.

No testing on this one yet. Seems solid though.

The Explorer - Your deck can't contain more than four copies of any basic land.

I had this when I played at Thanksgiving and I had a blast drafting a five color deck. This time Tod Semple (the Plants vs Zombies programmer) had it and didn't enjoy it much. Part of the problem was that M12 doesn't have much in the way of mana fixing, and he's not a particularly seasoned drafter so he likes being able to focus exclusively on two colors and just ignore the rest of the pack. Experienced players will enjoy this one I think.

The Fatalist - Before opening each pack, you must choose either "first 4" or "last 8". You must pick randomly for those picks during this pack.

No one had this one, but after thinking about it more I'm planning on changing the "before" to "after" (decisions are often more fun when you have more info), "first 4" to "first 3", and "last 8" to "last 9". The goal with the last two changes is to make it more of an interesting choice; I think with 4 and 8 you'll pick "last 8" almost every time since that still leaves you 7 strong picks per pack. With 3 and 9 I think you'll have to mix it up.

The Individualist - Your deck can't contain any two creatures with the same power and toughness or any two non-creature spells with the same mana cost.

This one suffered from some poor templating (it's fixed already above) which caused some confusion, so I didn't get particularly good data on it. I think it's one of the more interesting restrictions though.

The Jester - After opening each pack, choose odd or even. All cards selected during that pack must have that converted mana cost if possible.

Dylan, Stone's son, had this one and seemed to enjoy it. He started leaning towards odd once he realized that the basic land often prevented him from picking freely when he picked even (we counted zero as even) though. Maybe zero should count as neither so that it's a more balanced choice.

The Librarian - The name of every non-land card in your deck must start with a different letter.

Seems like this will work although no one had it.

The Opportunist - You may take two cards out of each pack that you open. You must play all of your cards except for the last and second to last picks.

This was a disaster. First because the player misread the restriction and thought he could take two cards with every single pick, and second because I balanced it terribly. I don't know why I thought the occasional double pick was enough to offset having to play 42 spells in your deck. I just didn't do the math. I'm not sure how I'm going to fix this one but I'll probably start with changing the last part to "except for the last five cards of each pack", giving them 30-33 spells.

The Pacifist - Your deck can't contain any cards that have a weapon in the art.

George Fan, the designer of Plants vs Zombies, had this one and chose to go for a green/blue Turbo Fog deck after picking up an early Rites of Flourishing. He hit an early snag when he realized that Fog hilariously has weapons in the art, and then another when he saw that Merfolk Mesmerist is carrying a wand, but he stuck with it and got a second Rites and four Jace's Erasures. He defeated all comers until running into my aggressive Pugilist deck and then later falling to the Individualist's Elixir of Immortality.

The Painter - You can't draft a card that's the same color as the last card you drafted, if possible.

Straightforward, seemed to work well. Also can reset the restriction by selecting the basic land. There's quite the competition for those lands!

The Pauper - You can't have any rares or mythics in your deck.

Gives you a lot of freedom at the cost of having to pass up some powerful cards. Rachel Reynolds had this and drafted an aggressive mono-blue deck that unfortunately lost to the Pacifist thanks to two Kraken's Eyes.

The Pugilist - Your deck can't contain cards that prevent opposing creatures from blocking your creatures (anything that grants flying, intimidate, protection, landwalk, etc).

I gladly kept this one and drafted an aggressive W/G deck featuring Sun Titan, Dungrove Elder and Overrun. There were numerous cards I couldn't take but I was still able to put together a solid deck and ended up going 4-0. I enjoyed how it made for very interactive games and there weren't very many stalemates at all.

The Sorcerer - Your deck can't contain more than nine creatures.

No one had this one. The condition seems solid but the number might need a bit of tweaking up or down.

The Storyteller - Non-land cards in your deck must have flavor text.

Not a terribly interesting condition in a base set draft since almost every single card seems to have it. Overall I like it though.

So that's the initial set. Overall they were a success but I plan to come up with some extra ones and start rotating them in and out and tweaking them as I go. Feel free to take these and try them out with your group. If you do, let me know how it went!

designing magic: planeswalkers & lorwyn

This is the fifth part of a series about working on Magic: the Gathering during my five years at Wizards of the Coast:

Part One (Joining WotC, playing in the FFL, developing Champions of Kamigawa)

Part Two (Developing Betrayers of Kamigawa and the Jitte mistake)

Part Three (Developing Ravnica, unleashing Friggorid, and designing MTGO Vanguard)

Part Four (Designing Ripple, the FFL during Time Spiral, designing Planar Chaos)

Future Sight

I wasn't involved in creating Future Sight, but I was a big contributor in a major debate that had started in one of our Tuesday Magic meetings, where everyone involved in Magic gets together to discuss the current major issues. The discussion revolved around the new card type that we were going to be debuting soon: Planeswalkers. The Future Sight team wanted to put a Planeswalker into their set, to increase excitement and foreshadow the "real" release of Planeswalkers coming in Lorwyn. I could see where they were coming from but it seemed like a terrible idea to me for several reasons:

- New things are exciting, but you only get that initial burst of excitement once. Why spend the Planeswalker excitement on Future Sight, a small set that already had a "hook" (these are cards from the future, some of which will become real later), when we could save it to sell our forthcoming large set? As much as people argued that the "real release" of Planeswalkers would still be Lorwyn, I knew that players wouldn't see it that way.

- Future Sight was already far above average in complexity and wackiness, thanks to a new card frame showcasing "future" cards like Steamflogger Boss. The set really didn't need a whole new card type for players to have to learn.

- The Planeswalker team needed more time. No one was completely happy with how they worked yet, and the balancing of a new card type was proving tricky. We had no idea of their power level and could've risked printing a completely unplayable Planeswalker or one that was far too strong.

In the end we compromised with referencing Planeswalkers on Tarmogoyf, a move that I think ended up being the best of both worlds. We foreshadowed Planeswalkers (and Tribal, for that matter) without actually showing our hand, which drove a lot of hype for the upcoming set. Of course, at that point no one had any idea that it would go on to become arguably the best green creature of all time.

Planeswalker Design

Around this time, Magic was going through somewhat of a creative reboot to make it more accessible and also better suited to supporting other potential media like books, graphic novels, or maybe even movies and TV. The goal was to have recognizable characters that could show up in multiple expansions (despite the different settings) that were relatable for players. Luckily, the IP already had an answer for this: Planeswalkers. And since the only way to get most Magic players to care about a character is to put a card depicting that character into their hands, it was time to add them to the game.

I was a part of the team tasked with figuring out what this new card type was going to do. Unfortunately I don't remember much about the process, but I do remember that one of the original designs had them following a list of instructions. They triggered on your upkeep I believe, and they would perform the first ability in the list on the first upkeep, then the second, then the third, and then they would wrap around and do the first ability again. We arrived at this because it didn't necessarily make sense to let you control another Planeswalker; it'd be like asking your friend to come play basketball with you and then having to direct their every move. With the ability list we encountered the opposite problem: they felt less like sentient beings and more like robots, especially when they performed an ability that didn't make sense with the game state, like giving a creature +4/+4 when you controlled no creatures.

We tried to get around this by giving them abilities that flowed into one another, like letting them create a creature before empowering it, but situations where the creature died in the meantime kept cropping up. Plus, it was sometimes hard to remember what step you were on, and marking them with tokens didn't work since you were already keeping track of their loyalty. Eventually someone hit on the idea of charging or granting loyalty for the abilities, and we changed it to let you choose which ability was activated. Then we let you activate them the turn you played them, which was a huge upgrade in terms of constructed quality and also just the overall feel. Suddenly playing a Planeswalker and having your opponent kill it on their turn didn't feel that bad.

Overall I think the Planeswalker card type was a huge success. I know that Richard Garfield has expressed concern about the amount of complexity that was added, and I agree with him that it's unfortunate that a new player can get a card that works so differently from everything else. At the end of the day, though, they provide some great gameplay, your opponents can interact with them (through burn spells or attacking them), and I think they've contributed to the recent success of Magic.

Lorwyn

The Lorwyn design team was Aaron Forsythe, Mark Rosewater, Brady Dommermuth, and Andrew Finch, with Nate Heiss replacing Andrew partway through. I can't say enough about how much I enjoyed working under Aaron. He's as well rounded as you could hope for: strong design skills, with the playskill and understanding of a developer, a huge knowledge of the game's history, and enough business sense that he's now been the director of Magic R&D for almost five years. What I enjoyed the most though is that he's one of those people who, at the end of the day, just wants what's best for the game. When everyone on a design team puts their egos aside and works as a unit towards that singular goal it can be quite the magical experience.

So much went on during Lorwyn design that I don't really know where to start, but I'll try to break it down into cohesive sections.

The Setting

Lorwyn takes place in an idyllic world filled with rolling pastures and beautiful forests. Where possible, we wanted to convey that through the cards and make the player feel the happiness and contentment of the world. One of the earliest ideas I had was to have a world without killing. Black wouldn't get any "destroy target creature" cards, and instead removal in this world would be themed as tricks and pranks, with the occasional application of -1/-1 counters. Using -1/-1 counters was potentially important because we knew that the last two sets in the block (Shadowmoor and Eventide) were going to be an evil version of the Lorwyn world, after a Cataclysm-type event, and at the time all of the sets in the same block had to use the exact same type of counters. There was just too much confusion from trying to support multiple different types of counters on the same card, and by keeping them out of the same block we at least kept those situations out of most sealed deck and draft experiences.

This turned out to be a terrible idea. Not only did it have the anticipated problems of causing frequent stalemates (we thought we could solve that by seeding certain types of cards into the set), but the slow application of -1/-1 counters actually made the set feel more evil than most. You weren't just cleanly killing creatures, you were torturing them to death over multiple turns. We went back to the drawing board, and soon found ourselves bringing up the problem at another one of the Tuesday Magic meetings. We lamented the fact that we couldn't use +1/+1 counters, and people started throwing out suggestions, but none of them seemed viable.

Eventually, as a joke, I said that this would be so much simpler if +1/+1 and -1/-1 counters would just annihilate each other, like matter and anti-matter. In hindsight, I guess there's no great reason why I thought it could never work, but as a designer you tend to quickly get used to the editor and rules manager telling you that ideas just can't possibly work within the rules. It's not that they're not good at their jobs, or that they're trying to stifle innovation, it's just that they're the ones who have to deal with all of the corner cases and who have to clean up the mess if anything breaks, and they're naturally a bit conservative. To my surprise, though, I saw them seriously considering it, and pretty quickly they said that it could function as a state-based effect. It didn't take long for the room to agree that with the support of that rules change, Lorwyn and Morningtide could use +1/+1 counters, and Shadowmoor and Eventide could use -1/-1 counters. Suddenly everything was so much easier.

Race and Class

Early in the process we had a meeting to decide the plan for the first half of the block. Specifically, what would we leave for Morningtide so that it would feel like it's own set and not just an extension of Lorwyn? It was a unique situation because there were only two sets to worry about; Shadowmoor and Eventide were doing their own thing (focusing on color) even though they would take place in the same physical location. I started thinking about how we had just recently done the race/class update, where all cards now had a race (a card that used to be just "Cleric" would now be "Human Cleric") and all sentient races now had a class (instead of just "Elf" it would be "Elf Warrior"). I knew we should take advantage of that somehow, and quickly I hit on the idea of having Lorwyn focus on the races like a traditional tribal set and Morningtide focus on the classes, which hadn't specifically been done before. Since the cards all had two types, and each race would be confined to only a few classes, new possibilities would open up for existing decks when the class tribal cards showed up in Morningtide. The team was on board with the plan and it never changed again.

The Tribal Supertype

We now knew how Morningtide would set itself apart, but that still left us to figure out how Lorwyn was different. We had all played Magic during Onslaught and enjoyed it, and we knew that just printing a bunch of cards with specific races and some other cards that enhanced them wouldn't be nearly as awesome the second time around. One idea that was rolling around, that I absolutely loved, was to apply the creature types to other types of spells. Essentially, not only would we have Elves, but we'd have Elven sorceries, Elven enchantments, Elven artifacts, and even Elven lands. This would solve one of those age-old problems of tribal decks, that you couldn't play any spells at all without diluting the tribal qualities of your deck. If you wanted 40 Goblins, you had to have 40 creatures.

We set out trying to figure out how this would work. What did it mean to be an Elf Instant? Certainly we could make cards that said "Whenever you play an Elf, get X" but it felt like the Elf instants themselves should be tied to Elves somehow. Some options I put forth:

- As an additional cost to play this spell, tap an untapped Elf you control.

- Play this spell only if you control an Elf.

- Tribalcycling

(

, discard this card: Search your library for a card that shares a subtype with this one, reveal it, and put it into your hand. Then shuffle your library.)

- If you tap an untapped Elf you control as you play this, use the Tribal effect instead. (e.g. +2/+2 or Tribal: +4/+4)

We went through the pros and cons of each of the team's suggestions, and eventually settled on the final one from the above list and calling it Mojo. It allowed you to play the spells even if you hadn't drawn any creatures yet still rewarded you for having the right type in play.

Next we moved forward with designing Mojo cards, at least until we hit the next snag. Mark Gottlieb came to us and told us that "Instant - Elf", which was how we were planning on templating the cards, wouldn't work. The game rules didn't allow creature subtypes on anything other than creatures. We tried debating, but there were a lot of subtleties he was worried about, like old cards that said something like "put an Elf from your hand into play." You can read about more about this process in Aaron's article about Lorwyn.

Aaron fought bravely for it but eventually saw the writing on the wall and gave in. Back to the drawing board.